“I used to think the years would go by in order, that you get older one year at a time. But it’s not like that. It happens overnight.”

– Haruki Murakami, Dance Dance Dance

Ageing Trends

The quote above may sound like a hyperbole, but it echoes a realistic challenge which many countries face these days – the issue of a rapid ageing population and how environments are struggling to catch up. According to the “World Ageing Population Highlights 2020” published by the United Nations, the world continues to experience an unprecedented and sustained change in the age structure of the global population, driven by increasing levels of life expectancy and decreasing levels of fertility.

Globally, there were 727 million persons aged 65 years or over in 2020. Over the next three decades, the number of older persons worldwide is projected to more than double, reaching over 1.5 billion in 2050. While the distribution of ageing population is more apparent in developed countries, the projections also indicate an uneven global distribution, with about two thirds of older adults’ population living in Asian region by 2050.

In Singapore, the infrastructural and social impact of ageing was exacerbated by the 1945 post war baby boom population and declining birth rates. The result is a much older working population, where the median age is now projected to be 54 by 2050. Because healthcare resources are limited, there is a parallel shift in healthcare distribution to cope with the increasing needs of older adults, where 3% of resources are dedicated in acute care, 7% in the community and 90% is targeting eldercare at home.

Environment and Ageing

The phenomenon of an aging world is not new, yet the core concern remains to be how the increase in the number of older adults is accompanied by a rise in the number of people with care needs. As architects, we are interested in how the home and built environment affects our health, yet the design challenges surface a level of complexity that requires architects to go beyond our traditional approach.

In the case of ageing, we study and design around the phenomena of the person-environment fit. Person-environment fit is the balance between environmental demands and a person’s ability to meet that demand and move comfortably and safely within the environment. If we are able to provide an assistive environment that reduces the environmental demands, we can maintain a person’s functional ability in old age that will enable wellbeing and quality of life.

Ageing in Place

In a survey released in February 2021 by the Housing Development Board of Singapore (HDB), results indicated that 86% of elderly residents intended to continue living in their existing flats, up from 80 per cent in 2013. Majority of the elderly residents surveyed expressed an emotional attachment to their current homes, having developed fond memories of the time spent with their family in the flat. Hence, our approach to eldercare is changing. Our focus is now moving towards ageing in place. Ageing in place is the ability to live in one’s home and community safely and independently, with the closest person-environment fit – where the environment does not negatively impact a person’s functional ability. Because older adults spend more time at home than any other age group, the home and neighbourhood environment are more likely to exert increasing influence on their mobility and social interactions.

CPG’s Approach to Healthcare Design for Ageing

Integrated Design Thinking

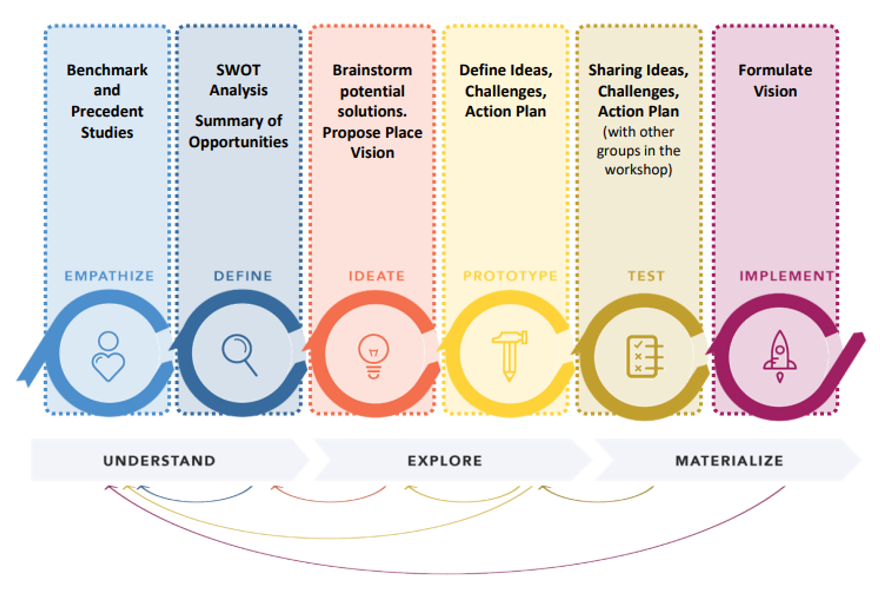

Integrated Design thinking process (Diagram by CPG Consultants)

Hence, a critical component of our design process involves integrated design thinking at the core of our practice. Integrated design thinking is the comprehensive and iterative process to derive the best design strategies, consistently striving to areas of improvement from initial design to completion. Integrated design thinking is accomplished by involving feedback from various stakeholders (developers, various consultants, end-users, and the community) at all stages of the project. In doing so, we can address the current issues and co-create a project framework to materialise the vision.

The Land and Liveability National Innovation Challenge

A case study of how our CPG Healthcare Division employed integrated design thinking in our work is the Land and Liveability National Innovation Challenge Initiative. This was a research-based design project to develop age-friendly neighborhoods in Singapore. The project was a joint effort by the CPG Healthcare Division and the CPG Urban Planning team, who collaborated with the Singapore University of Technology and Design and the Geriatric Education & Research Institute (GERI). The study used the integrated design thinking approach to investigate the site needs, develop a common consensus on project goals, and co-create design solutions to address the older adults needs in the neighbourhood.

Chosen as the study site was Hong Kah North, located in the Western Part of Singapore. 30% of the population are aged 55 years and above and the estate was officially announced as to be Singapore’s second dementia-friendly community in 2016. Since the estate was developed in the 1980s, majority of the buildings were aged between 30 to 35 years, and were not specifically designed for an ageing population. Hence the research investigated areas in the neighborhood where design intervention could address the needs of older adults in the community.

There are 6 zones in Hong Kah North and some of the site conditions that posed a challenge for ageing individuals. We discovered that the estate proved a challenge to older adults’ safety and access to recreational walking spaces and community activities. There is no clear designated pedestrian access, with most of pedestrian pathways located along the road and/or part of Park Connector Network (PCN).

Likewise, changes in ground levels were not mitigated with ramp which posed a fall hazard for older adults and physically impaired. Furthermore, with regards to cognitive assistance, the estate lacked clear wayfinding markers to support older adults’ navigation within the neighborhood. Without distinct character or identity of each zone, the neighborhood design made it less likely for older adults with cognitive impairment to engage in community activities or recreational walking.

Community Workshops

To design for ageing-in-place, it is useful to engage older adults in the community to be part of the design process so that we can derive sensitive, responsive, and useful design strategies that prioritise the lived experience of the older adults from a vernacular standpoint instead of a clinical, top-down approach. In the case of Hong Kah North, to get a deeper understanding of the community’s needs, we conducted a round of workshops to engage residents on design strategies to improve their neighbourhood and introduce age friendly solutions. The dialogue from residents, designers, and researchers fostered dynamic design solutions that responded to the communal goal of creating an age-friendly, inclusive neighbourhood.

Community workshops with Hong Kah North residents (Photos: CPG Consultants)

Co-created framework

The participatory approach led to 3 main design principles targeting 1) community spaces (2) street furniture, and (3) wayfinding. Community spaces (activities and programs) should cater to the preferences of residents and encourage social interactions, such as designing areas for community dances, morning tai chi, social gardening etc. Street furniture are a necessary affordance to support older adults’ everyday routines and encourage recreational walking. By incorporating street furniture into the urban planning design of Hong Kah North, the walking networks can support older adults’ active lifestyle, and encourage them to spend more time outside of their homes. Lastly, the study established that wayfinding markers were integral to Hong Kah North upgrade to assist older adults with orientation and independent mobility. After implementing a series of prototype in Hong Kah North, the end results of the study were age-friendly design strategies that could be incorporated and scaled up for application in similar housing estates across Singapore.

Examples of design features which cater to residents’ living habits (Diagram by CPG Consultants)

Future planning of homes for ageing in place

Endemic living means we may be spending more time at home and our built environment needs to be designed to support healthier, more resilient homes. With the rise of telemedicine and technology, that connection between the home and critical care institutions is becoming more symbiotic. For example, technology can help older adults with chronic conditions like diabetes or fall related injuries to easily upload their progress to their case managers from their homes via their smart phones. To keep up with our advancing needs, our homes have to get smarter, healthier and play a more critical role in supporting quality of life.

Utilising technology can create an open conversation between residents and caregivers, by breaking down the institutional wall that separates our homes from sources of care and wellbeing. Healthy housing will ensure that urban cities like Singapore is better equipped to meet the needs of older adults. It also breaks the stereotype that healthcare design is only for a hospital. Designing our communities to be age friendly brings wellbeing into our everyday lives, allowing us to live, work, play and grow old with a greater sense of attachment and appreciation to our environment.

For more information, reach out to CPG's Healthcare Division:

Ar. Frankie Lim Lip Chuan, Senior Vice President

Architecture Group, CPG Consultants Pte. Ltd.

lim.lip.chuan@cpgcorp.com.sg

Ar. Jerry Ong, Senior Vice President

Architecture Group, CPG Consultants Pte. Ltd.

jerry.ong@cpgcorp.com.sg